By Jennifer Berry Hawes, Seanna Adcox and Libby Stanford with The Post and Courier

May 22, 2021

The mantra became accepted wisdom: South Carolina’s public schools have struggled for decades due to a crippling lack of money. And what they did get was hampered by enough bureaucratic morass to stifle any whiff of innovation.

Student test scores fell behind. Racial disparities widened. School buildings crumbled.

But now a deluge of federal COVID-19 relief money is giving local school boards a nearly $3 billion opportunity to change that. If they use it wisely, the historic cash flow could transform education as we know it in South Carolina.

If they don’t, they will have wasted a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity — maybe two or three lifetimes — and substantiated every excuse the state Legislature has ever given for not sending them more resources: waste, incompetence, and corruption.

“That’s what will keep me up at night and terrify me,” said Patrick Kelly, a high school history teacher and lobbyist for the Palmetto State Teachers Association. “If schools don’t move the needle on student achievement over the next two years, then I get really worried.”

The sheer volume of money is more than three times what public schools normally get from the federal government. And it’s flowing into local district coffers with little oversight.

State legislators can’t touch it. Nor can they let it supplant state spending. The state Department of Education can only make sure the spending is legal under federal law, which gives broad categories for its use.

Instead, accountability for the infusion of cash rests with local school boards — elected officials who often bring neither teaching experience nor financial expertise. They run the gamut of effective arbiters of education to toxic partisans.

Even the most adept boards have scant experience handling this volume of money, a sudden deluge that will dry up in 2024.

Justin Farnsworth, who sits on the Dorchester District 2 board, said they just want to “make sure we get the best bang for the buck and not put ourselves in a hole for future years.”

The influx of money comes several years after a Post and Courier investigation in 2018 called Minimally Adequate, which detailed how the state’s schools remained mired in inequities. As a whole, they trailed other states in nearly every measure. While lawmakers shirked their own funding requirements, gaps in achievement and resources widened.

After the series ran, lawmakers pledged to overhaul the tangled, antiquated way the state funds public schools and direct more money to classrooms. As promised, House Speaker Jay Lucas introduced a massive, 84-page bill in January 2019 aimed at beginning to transform the system, though it didn’t touch funding formulas. That was supposed to be next.

The bill quickly met backlash from teachers in the newly formed advocacy group SC for Ed, who complained the bill was written without their input. They fought hard to kill it and start over.

The state House overwhelmingly passed the bill anyway in March 2019. The Senate passed its own vastly different version a year later — in March 2020.

And then COVID hit.

The larger effort floundered, although pieces of it have passed since, or will soon. Teachers got their largest pay hike in 35 years. And an upcoming vote could expand state-paid, full-day kindergarten to all at-risk 4-year-olds.

Yet, the $3 billion coming down the pike could impact schools far more than the big reform bill might have.

For teachers, the enormity of relief matches the enormity of their exhaustion.

Since March 2020, they have traversed a gantlet of ever-changing rules. They juggled in-person and online teaching. They watched parents and politicians spar over face masks. They counseled students struggling with worsening mental health problems — all while grappling with their own fears of contracting the virus.

“It’s been nonstop,” fourth grade Anderson County teacher Justus Cox said. “We all feel it.”

Meanwhile, more students fell behind.

Only 30 percent of the state’s third through eighth graders are now projected to meet grade-level proficiency in math and English.

That’s why The Post and Courier is launching a new ongoing investigation called Promises. It will follow the massive amount of federal aid flowing into local districts to see how their school boards spend the money — and what outcomes they achieve with it.

As state Education Superintendent Molly Spearman told the newspaper in 2018: “We keep kicking the can down the road and keeping things like they are. I don’t know if we can ever get everybody to sit down at the table and really change it.”

Now, they have to. The race is on to figure out how to spend so much money.

As Spearman told the newspaper last week: “It’s an opportunity we’ve never had before.”

Making plans

South Carolina’s school districts will get $2.94 billion total from three packages of COVID relief money approved by Congress since the pandemic began.

So far, districts across South Carolina have spent just under 70 percent of the $194.7 million Congress allotted in the first aid package from when the coronavirus first forced schools and businesses to shut down.

They have spent less than 1 percent of the $846.4 million they will get from the second wave. Roughly one in four of the state’s 79 traditional school districts still haven’t even submitted plans for spending it. No-shows include the state’s two largest districts: Charleston and Greenville counties.

And now comes the third — and largest — wave. It will make for a busy summer.

Two-thirds of the $1.9 billion in this latest package will flow into the state on Monday, and local districts can start drawing from it then. Four days later, the deadline will loom for districts to send Spearman’s office their strategies for catching up students who have fallen behind.

The state will use those strategies to craft its overall plan, due to the federal government June 7. The rest of the money will become available when the state’s plan is approved.

“It’s a quickly winding clock,” Kelly, the high school teacher, said. “The money we are talking about coming in is not only beyond a district’s federal allocation but starting to push doubling a district’s budget. They’re not staffed to deal with that money.”

And many school districts already struggled with financial acumen, even before the pandemic hit.

Spearman has assumed management of three rural school districts since 2017 due to abysmal academic performance — and financial ills.

In February 2019, she also declared a fiscal emergency in a fourth, Sumter County, publicly putting that district on warning the state might take it over, too. With budgeting help, the county rid itself of that emergency designation last year.

Then last fall, Spearman declared a financial takeover of Clarendon District 1 in Summerton. The district was operating in the red and had failed to withhold taxes or pay into employees’ retirement.

Blame and finger-pointing over schools’ financial woes aren’t new. They have persisted over the past two-plus decades as the state’s academic performance fell from bad to worse, to dead last in some measures, behind even Mississippi.

School boards faulted legislators for shortchanging them. Legislators faulted school boards for making bad decisions locally.

Amid that blame game comes the chance to make real progress, especially for students who most need the help.

At least 20 percent of the relief money from Congress’ latest aid package must help catch students up academically from so-called “COVID slide,” learning lost to the pandemic.

Like all states, South Carolina suspended standardized testing last spring. But, beginning last summer, districts administered other tests that gauge individual student growth.

The results are troubling.

Seven in 10 students in third through eighth grades aren’t projected to meet grade-level proficiency in math and English language arts. And fall-to-winter growth was far below what is expected in all grades for reading and for most grades in math.

After COVID forced the sudden closure of schools, districts created a hodgepodge of remote learning efforts. Some students connected to their teachers online while others relied solely on paper-packet instruction picked up and dropped off weekly.

And tens of thousands of students stopped communicating with their teachers altogether for the rest of the school year.

Now districts must figure out how to reboot and meet their needs — quickly.

The “academic recovery plans” due to Spearman’s office on May 28 must explain how districts will help students who fall into three levels, from a little to significantly behind, using their own testing data. They can include tactics like “high-dosage” one-on-one tutoring, year-round calendars and promoting students to the next grade but keeping them with their same teacher as last year.

More detailed plans are due in late August, after school districts seek public input on how to spend the money.

“Some districts are struggling,” said Jon Butzon, a state Board of Education member and former director of the Charleston Education Network. “They don’t know how to write a plan. They’re not sure how to get their heads around it.”

Spearman said guidance from her agency includes frequent webinars and an assigned coordinator to each district whose full-time job is to help local officials develop strategies and budget their plans. The office is hiring four more coordinators, for a total of 10, who will be part of a new division.

Although her agency can’t force districts to take the advice offered, “We are telling them if they do something with the money they’re not supposed to, they have to pay it back.”

Her staff will be tasked with oversight — but it will come on the back end and won’t focus on whether districts spent the money effectively. Instead, monitoring will include whether districts followed their own rules for things like procurement and whether receipts match what they reported they bought.

Meeting Street model

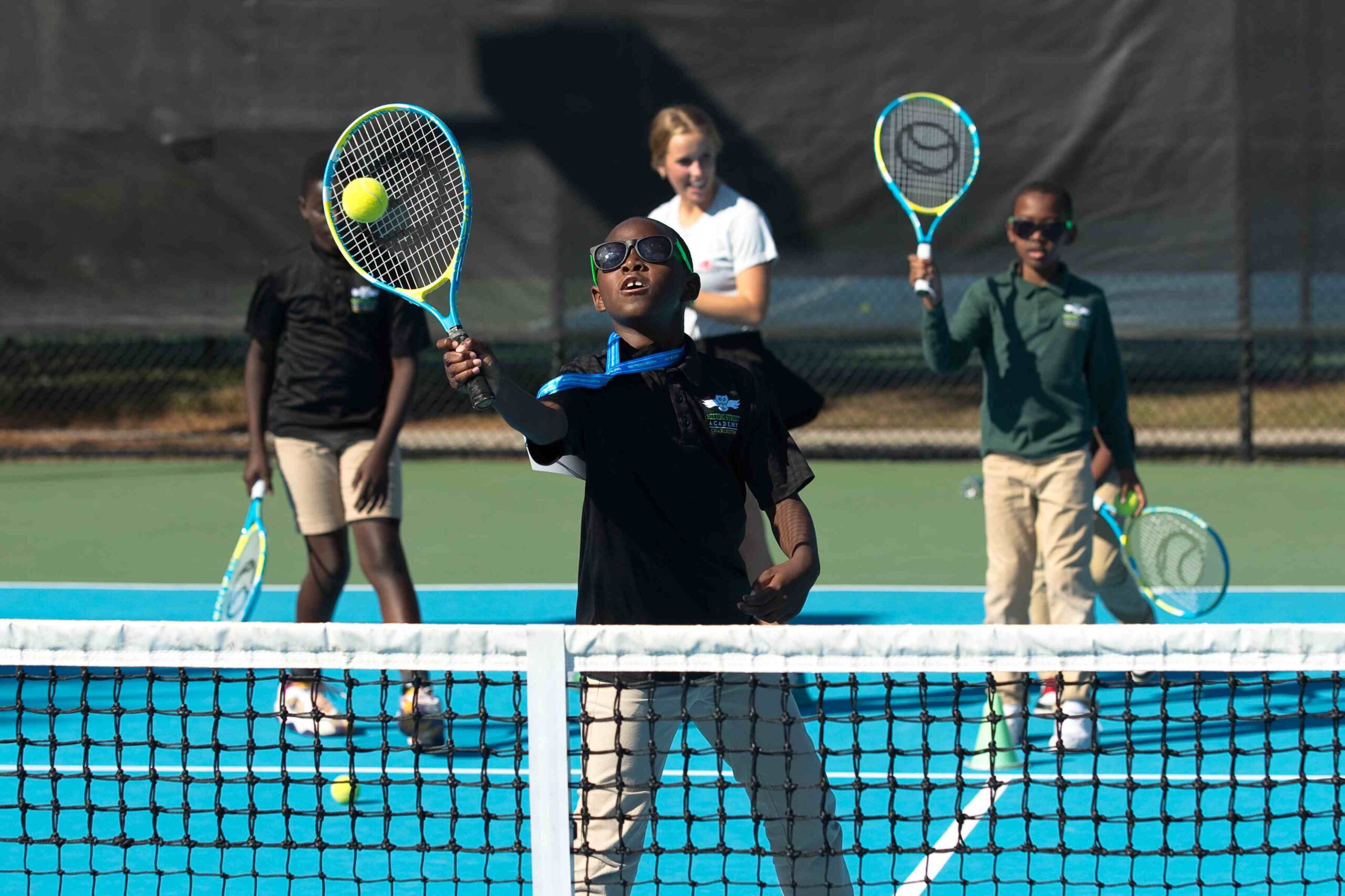

The phones at Meeting Street Schools have been ringing more than usual. Districts across the state want to know how its schools have boosted student performance using an infusion of extra money.

Meeting Street runs three public-private elementary schools: two in North Charleston and one in Spartanburg. They all get the usual per-student state and federal dollars. But they also receive another 5 to 15 percent more from companies like Boeing and individuals including its founders, Charleston businessman Ben Navarro and his wife Kelly.

And that money has given its schools a leg up with the kinds of improvements other schools are now considering with their COVID relief money: two teachers per classroom, comprehensive mental health and social-emotional support, and extended learning time in the form of afterschool and summer programs.

The schools’ data shows the impact of those additions.

At Meeting Street Elementary @Brentwood in North Charleston, for instance, students placed in the 73rd percentile in math and 53rd percentile for reading. That far outperforms other elementary schools with similar poverty levels in North Charleston, which averaged in the 23rd percentile for both reading and math, according to data collected in 2018. That is the most recent available.

Even before the latest round of COVID relief money, more districts had begun to consider creating public-private schools like those operated by Meeting Street. Lawmakers made it more doable last month with a bill that got overwhelming support in both chambers.

On April 23, Gov. Henry McMaster signed the bill, which allows school districts to operate multiple “schools of innovation,” which get more flexibility from state laws and regulations.

Couple that with passage of the latest federal COVID aid package, and Meeting Street CEO Christopher Ruszkowski has been hearing from superintendents. They want to know how to follow its model.

“The stimulus provides an opportunity for recovery but also some degree of reinvention as well,” he said.

Leona Davis attended Burns Elementary before it partnered with Meeting Street. Davis, whose niece is a fourth grader there now, said the difference is night and day.

She is especially grateful for the school’s two-teacher model, which pairs a new teacher with a veteran in its classrooms. Her niece’s teachers have her phone number in case anything goes wrong, and she feels close relationships with them.

“The involvement that they have with the students and our families is so phenomenal,” Davis said. “There’s no comparison to it. The children are loved and at the same time the parents are aware of everything that goes on in the school.”

Meaningful changes

Over the next three years, South Carolina and other states can try many upgrades normally out of financial reach.

But some educators worry that 79 districts might do 79 different things. School administrators are already getting bombarded by companies eager to sell them their products.

“We have to be really careful to avoid these disjointed initiatives — something here, something there, something someplace else — that doesn’t form a cohesive and comprehensive approach,” Charleston County School District superintendent Gerrita Postlewait said.

Charleston County will have $249.2 million total to spend on its approach, second only to Greenville County’s $254.6 million share.

Recent Post and Courier interviews with teachers and other education experts yielded key areas most would like districts to focus on:

• Two teachers per classroom

Intensive instruction tops the list. And few ideas get more support than two teachers per classroom, especially for younger students.

Cox, the fourth-grade teacher, works at Varennes Elementary School, a high-poverty school in Anderson. He is starting his fifth year teaching and about to finish his master’s degree.

Pairing new teachers with experienced ones in a classroom could boost retention significantly, he said.

“We are thrown into the fire,” he said. “We can read all the theories and all the great psychology, but you’re not going to really learn until you’re in that room. That’s the part we’re missing.”

However, the federal money will dry up in three years. Schools can’t go out and hire 1,000 new teachers only to lay them off then.

The state’s severe teacher shortage won’t help either. Already at crisis level, the shortage worsened amid the pandemic, as fewer hires over the summer created a spike in vacancies when the school year started. As of February, 515 openings remained across South Carolina, representing 1 percent of the state’s K-12 teaching positions, according to the state Center for Educator Recruitment, Retention and Advancement.

But lawmakers recently made it more lucrative for retired teachers to jump back in.

And Kelly offered a novel idea: tap third-year college education majors, the state’s future teachers. They could take a gap year to work as the second teachers in classrooms.

That would give established teachers help — and the student teachers invaluable classroom experience. Districts would pay them with COVID aid money and could throw in senior year tuition payment to lure them to schools most in need.

This strategy also could yield a trove of data to gauge how much impact two teachers make on a broader range of students than Meeting Street schools alone can provide.

“Here’s the case study,” Kelly said. “For the next two years, let’s lean in on those things we’ve said we should try.”

• Mental health assistance

Given the pandemic’s toll, students desperately need more access to mental health professionals.

“The mental health crisis is growing and is real in schools right now,” Kelly said.

Most students who receive mental health care get it through their schools, yet entire school districts lack even a single full-time psychologist.

National guidelines for guidance counselors recommend one per 250 students. In South Carolina, schools run closer to one per 347.

• Summer and afterschool programs

One of the state’s foremost schools experts is Terry Peterson, who served as chief education adviser to Richard Riley, a former U.S. education secretary and South Carolina governor.

Peterson has long extolled the need for quality summer and after-school programs. This includes camps, career and college exploration, and apprentice-style projects.

Now, he is advising groups in about eight states to consider their best use of the COVID relief money. He hopes South Carolina schools will use their funds this way and points to two local groups already offering this type of help: Engaging Creative Minds and WINGS for Kids.

Dorchester District 2 is among many districts targeting major chunks of the new money at summer learning, Superintendent Joe Pye said.

The district will receive a total of $62.1 million from the three waves of funding. It will use the third one, about $40.5 million, to help pay teachers for summer math and reading camps through 2024.

“This may not solve the problems totally,” Pye said, “but it will certainly keep things moving along.”

The road ahead

Unable to dictate local decisions, Spearman plans to promote certain ideas with an offer districts “would be foolish not to take advantage of,” she said: a slice of the $327 million her agency will get in federal COVID aid, in the form of matching funds for ideas proven to work.

“That is the extent of what we’re able to do,” she said. “So, we’re going to be using that tactic.”

This summer, districts must seek public input for spending the money coming their way. Given the opportunity for big changes, Spearman urged the public to get engaged. Attend public board meetings. Ask questions.

And don’t wait for local districts to hand out their spending proposals. Federal law doesn’t require the boards post their third-wave plans for the public to see until they already are finalized and approved — right as the next school year begins.

Copyright 2021 The Post and Courier. All rights reserved.